I had a bad case of Kierkegaard in college.

My diagnosis was directly attributable to Sister Mary Clare, my high school principal at Immaculata Prep.

You see — from my Jesuit educated dad, I inherited an insatiable curiosity and an inquiring mind. Virtually all my sentences ended in question marks – especially in religion class.

“Transubstantiation makes no sense, Sister. Why would Jesus want us to eat him?”

“The atonement? Why does God kill his only son to save us? What kind of God is that?”

“Bad Catholics go to heaven? Loving Buddhists go to hell? What’s up with that?”

And the deepest and most disturbing question: “Why is French kissing a mortal sin?”

Called into the principal’s office, Sister Mary Clare sat me down to set me straight.

“Joani, you have to stop asking questions in religion class. You are confusing the other girls.”

“Joani, you are intellectually gifted but you are spiritually r******d.”

Yes, “spiritually r******d”. That’s a direct quote.

So I skipped my senior year (for more than just this reason) to become a philosophy major at Catholic University — a philosophy major who could ask all the f*ing questions she wanted.

I loved my three years at Catholic U. Historically we read the greatest thinkers of all times: ancient, medieval, modern, existentialist and more.

We didn’t read about philosophy, we read the philosophers themselves: Plato, Aristotle, Plotinus, Boethius, Aquinas, Descartes, Kant, Hume, Heidegger, Hegel, Spinoza, Levinas, Wittgenstein, Sartre – and of course Kierkegaard. (Achoo!)

And because I left in my final year without finishing, I missed out on a generation or two of 20th century thinkers: Foucault, Derrida, etc.

But what I did not miss out on was a first class education. Philosophy not only exercises the brain and challenges the mind – philosophy is a balm for fevered souls.

I aced logic and excelled at metaphysics. I ached with existential angst. I entered Catholic U a parochial school girl and by the time I left I was a Platonic, Hegelian, Enlightened, Phenomenological Agnostic.

(What does that mean? I don’t exactly know.)

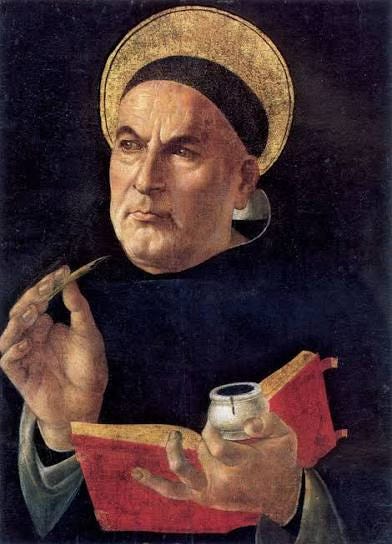

Decades later, I could not now pass a philosophy exam to save my life, but there is a particular thread in medieval and early modern thinking that I believe deserves our attention: the Just War Theory of Thomas Aquinas.

Centuries old, the theory itself has been critiqued for centuries. But Aquinas still speaks much wisdom in the midst of our current existential crisis.

As you read it through, think of WWI and WWII.

As you read it through, think of Korea and Vietnam.

As you read it through, think of more recent Middle East wars in Afghanistan, Syria, and Iraq.

As you read it through, think about Ukraine having been invaded by Russia.

As you read it through, think about Israel’s devastation of Gaza.

As you read it through, think about Trump joining in with Netanyahu to drop bombs on Iran.

Read it through and come to your own conclusions.

Thomas Aquinas – Just War Theory from Summa Theologiae II-II, q. 40.

General Principles:

War is justified (nation A wars justly against nation B) on the following conditions:

A. It is called by a sovereign authority.

B. It has a just cause.

C. The combatants have morally right intentions (not vengeance or profit – see below).

D. Qualifying Conditions (from the theory of double-effect on his justification of killing in self-defense: ST II-II, 64, 7).

Cannot intend intrinsically evil actions.

A good action, or at least a morally neutral action, will have two effects: a good intended, and an evil, not intended, but tolerated.

Proportionality: the good to be achieved outweighs the evil of war.

The bullet points boil Aquinas’ theory down to its essence. But ethically it’s incredibly COMPLICATED, so aquinasonline.com offers some clarification.

A. A Just War must be called by a sovereign authority. It is a nation (not individuals) who declares war.

wars are just when they are in defense of the common goods.

the sovereign has care for the common good (of a particular nation)

when private citizens, either individually or in groups, take up arms to oppose the common good, they are not engaged in war, but in the sin of sedition and oppose the unity and peace of a people. (ST II-II, q. 42)

a. the sin of sedition applies “not only in him who sows discord, but also in those who dissent from one another inordinately” by following the fomenters of sedition (a. 1, ad 1)

b. the violenceof a people is always wrong when “it is contrary to the unity of the multitude, which is a manifest good.” (a. 2, ad 2)

c. opposition to a tyrant can be permissible (a. 2 ad 3)

i. “a tyrannical government is not just, because it is directed, not to the common good, but to the private good of the ruler.”

ii. resistance to a tyrant is not permissible if “the tyrant’s rule be disturbed so inordinately, that his subjects suffer greater harm from the consequent disturbance than from the tyrant’s government” (i.e., if the violence is disproportionate to the common good lost to tyranny.)

B. Just Cause

Thomas Aquinas addresses causes which concern the nation (nation A) itself.

a. An enemy (nation B) is attacked because they deserve it.

b. The enemy is guilty of some fault.

c. A nation may war justly

i. To avenge a wrong.

ii. Punish enemy for refusing to make amends for some past fault.

iii. To restore what was seized unjustly.Later thinkers have expanded the notion of just cause. (See ‘The Just War’ by Jonathan Barnes in The Cambridge History of Later Medieval Philosophy(1982), pp. 771-785.)

a. Is war justified when someone other than the warring nation suffered from an enemy’s unjust aggression?

i. Friends and allies: Nation A may justly war on nation B to defend nation C. (See Thomas Aquinas, ST II-II, 188, 3 ad 1)

ii. The inhabitants of the enemy country (nation B) [a war of liberation].

a) St. Thomas More (1535) – Yes, war may be justified for humanitarian reasons.

b) Francisco Suarez (1617) – No, such a war violates the sovereignty of the other nation and will lead to international chaos.

b. There has not been any actual aggression from the enemy, but nation A has reason to fear that there is a threat of an attack from nation B [a pre-emptive war].

i. Francisco de Vitoria (1546) – No, wars are just only when redressing actual injustice.

ii. Francis Bacon (1626) – Yes, just fear is a lawful cause for war.

iii. Hugo Grotius (1645) – To threaten one’s neighbors is an actual injustice; it is aggression against peaceful order between nations.

C. The combatants in a just war must have right intentions.

advancement of good and the avoidance of evil.

unjust reasons include

a. Greed.

b. Cruelty.

c. Vengeance.just reasons include

a. Secure peace.

b. Punish evil-doers.

c. Uplifting of good.

D. Qualifying Conditions – from the justification of self-defense and the theory of double-effect.

Cannot intend intrinsically evil actions: Combatants must respect non-combatants.

a. Combatants who cease to be such.

i. Surrendering.

ii. Wounded.

b. A nation can never justly target civilians.

i. Civilian casualties, while foreseeable, cannot be intended.

ii. Measures must be taken to minimize civilian casualties.The violence inherent in war is the tolerated evil secondary effect, never directly intended; the primary good effect of peace must be directly intended.

Proportionality: the good to be achieved outweighs the evil of war.

a. One cannot war justly over a slight cause.

(i. War is a last resort.)

(ii. There must be a reasonable hope of success; one cannot engage in justified, but hopeless actions.)

b. One may only use the minimal force necessary to achieve just ends.

Having read it though, think it through.

Make your thoughts known to the powers that be.

Act accordingly.